Featured

This Months Feature —

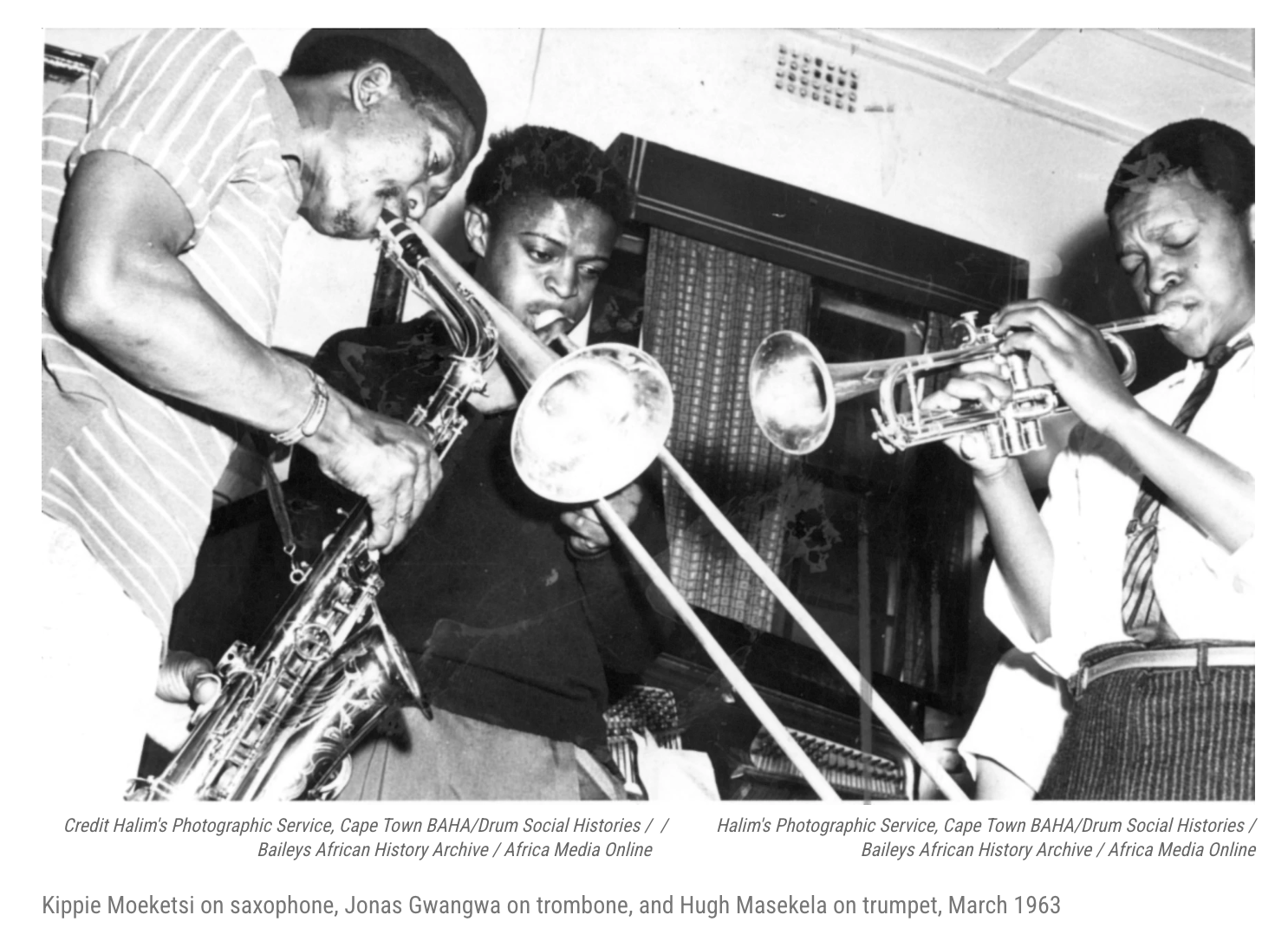

Kippie Moeketsi on saxophone, Jonas Gwangwa on trombone, and Hugh Masekela on trumpet, March 1963.

A Moment in South African Jazz History

March 1963 captures a rare and telling convergence in South African jazz history. Kippie Moeketsi on saxophone, Jonas

Gwangwa on trombone, and Hugh Masekela on trumpet appear together at a pivotal moment. The image represents not merely a

lineup of exceptional instrumentalists, but a generation of artists whose music carried cultural memory, resistance and

aspiration during one of South Africa’s most repressive political eras.

Historical Context

By 1963, apartheid had entered an intensified phase. The Sharpeville Massacre lay three years in the past, political

organizations had been banned, and artists increasingly found themselves under surveillance or forced into exile. Jazz

musicians occupied a precarious position, celebrated for their artistry yet constrained by segregation laws that

controlled movement, performance and association.

Within this environment, jazz functioned as both refuge and resistance. Performances became acts of defiance and

rehearsals acts of preservation. The gathering of Moeketsi, Gwangwa and Masekela in March 1963 reflects a final

flowering of an extraordinary local scene before the mass departure of South African jazz talent accelerated abroad.

The Musicians

Kippie Moeketsi, widely regarded as the father of South African jazz, was a central architect of the country’s modern

jazz language. His alto saxophone style fused bebop fluency with township phrasing, establishing an idiom that would

shape generations to come. By 1963, Moeketsi’s sound was fully formed, lyrical, restless and unmistakably local.

Jonas Gwangwa, then early in his international ascent, brought a bold and harmonically adventurous trombone voice. His

playing bridged big band sensibility with small ensemble exploration, while his compositional instincts already

suggested the large scale works he would later produce in exile.

Hugh Masekela, on the verge of global recognition, played trumpet with clarity and brilliance that carried deep

emotional weight. His tone was direct, singing and distinctly African, and though his international career was imminent,

in 1963 his music remained closely tied to the immediacy of the South African experience.

Musical Significance

The combination of saxophone, trombone and trumpet evokes the frontline of a horn ensemble, a format suited to dialogue,

call and response and collective improvisation. In these settings, the musicians functioned not only as soloists but as

conversationalists, shaping musical statements that reflected social realities such as tension and release, assertion

and restraint.

The importance of this moment lies not in a specific recording, but in its symbolic weight. Each musician would soon

follow a different path, some into exile, some into declining health, all into legend. March 1963 stands as a threshold

between an era rooted in South African soil and a global dispersal that carried its sound to the world.

Legacy

Today, this moment endures as archival testimony to a generation that transformed adversity into art. Moeketsi’s

foundational influence, Gwangwa’s compositional reach and Masekela’s global advocacy collectively define the DNA of

South African jazz.

March 1963 is remembered not for spectacle, but for presence. Three horns, three voices and a shared commitment to music

as cultural record and instrument of survival.

This Months Feature —

Kippie Moeketsi on saxophone, Jonas Gwangwa on trombone, and Hugh Masekela on trumpet, March 1963.

A Moment in South African Jazz History

March 1963 captures a rare and telling convergence in South African jazz history. Kippie Moeketsi on saxophone, Jonas

Gwangwa on trombone, and Hugh Masekela on trumpet appear together at a pivotal moment. The image represents not merely a

lineup of exceptional instrumentalists, but a generation of artists whose music carried cultural memory, resistance and

aspiration during one of South Africa’s most repressive political eras.

Historical Context

By 1963, apartheid had entered an intensified phase. The Sharpeville Massacre lay three years in the past, political

organizations had been banned, and artists increasingly found themselves under surveillance or forced into exile. Jazz

musicians occupied a precarious position, celebrated for their artistry yet constrained by segregation laws that

controlled movement, performance and association.

Within this environment, jazz functioned as both refuge and resistance. Performances became acts of defiance and

rehearsals acts of preservation. The gathering of Moeketsi, Gwangwa and Masekela in March 1963 reflects a final

flowering of an extraordinary local scene before the mass departure of South African jazz talent accelerated abroad.

The Musicians

Kippie Moeketsi, widely regarded as the father of South African jazz, was a central architect of the country’s modern

jazz language. His alto saxophone style fused bebop fluency with township phrasing, establishing an idiom that would

shape generations to come. By 1963, Moeketsi’s sound was fully formed, lyrical, restless and unmistakably local.

Jonas Gwangwa, then early in his international ascent, brought a bold and harmonically adventurous trombone voice. His

playing bridged big band sensibility with small ensemble exploration, while his compositional instincts already

suggested the large scale works he would later produce in exile.

Hugh Masekela, on the verge of global recognition, played trumpet with clarity and brilliance that carried deep

emotional weight. His tone was direct, singing and distinctly African, and though his international career was imminent,

in 1963 his music remained closely tied to the immediacy of the South African experience.

Musical Significance

The combination of saxophone, trombone and trumpet evokes the frontline of a horn ensemble, a format suited to dialogue,

call and response and collective improvisation. In these settings, the musicians functioned not only as soloists but as

conversationalists, shaping musical statements that reflected social realities such as tension and release, assertion

and restraint.

The importance of this moment lies not in a specific recording, but in its symbolic weight. Each musician would soon

follow a different path, some into exile, some into declining health, all into legend. March 1963 stands as a threshold

between an era rooted in South African soil and a global dispersal that carried its sound to the world.

Legacy

Today, this moment endures as archival testimony to a generation that transformed adversity into art. Moeketsi’s

foundational influence, Gwangwa’s compositional reach and Masekela’s global advocacy collectively define the DNA of

South African jazz.

March 1963 is remembered not for spectacle, but for presence. Three horns, three voices and a shared commitment to music

as cultural record and instrument of survival.